|

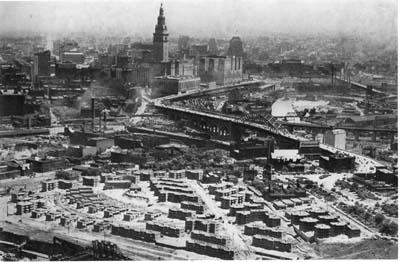

Cleveland during the Great Depression of the 1930s If Hegel had lived long enough he might have used Cleveland in the 1930s to illustrate his dialectical philosophy. With some help from Kant, Hegel established a view of history as clashes between inevitable opposites. Any happening, he said, creates its opposite. Antagonisms between them bring about change. In the mid-19th century, about when Hegel died, Cleveland's leaders started importing laborers from Ireland, Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe. Those leaders were White Anglo-Saxon Protestants whose deepest beliefs were often offended by the laborers, who were usually poverty-stricken Catholics. Though Cleveland's WASPs looked down on their hired hands as cultural inferiors, they had no choice but to use them for building a powerful industrial and commercial city, an imperative dictated by their religious culture. Protestantism, especially after it was inspired by Calvinism, embraced a new perspective on wealth: it should be invested rather than merely displayed. Capitalism and Protestantism were made for each other. In the second half of the 19th century, investments and using cheap labor in mass amounts to produce industrial products became a good protestant's road to salvation. The number of eastern Europeans settling in Cleveland after 1850 was phenomenal, the largest collection outside of Eastern Europe itself. There were more foreign-language newspapers in Cleveland than any other city in the world and each ethnic group had a weekend radio "hour". So it was that a grand cultural and economic conflict began between Cleveland's well-heeled Protestants and sometimes-shoeless Catholic immigrants. The outcome was as Hegel would have expected, but it would have disappointed Karl Marx. Marx had given a twist to Hegel. There would be one final contradiction between capitalists and labor, in which laborers would "throw off their chains" and kick capitalists off the planet. Communism would reign and that would be the end of history. I grew up during the final battleground years of the capitalism/labor struggle. Hegel said that contradictions can simmer for years before some specific happening highlights their stark incompatibilities. The Great

Depression was such a happening. It revealed the misery workers could suffer when something goes wrong for capitalism. During World War I American workers enjoyed a sharp increase in wages. In the twenties everything, including workers' wages, coasted on bubbles of pseudo-prosperity. Then the bubbles burst.

Catholic parish schools were in the thick of this final battleground because a pivotal controversial issue in the 1930s was how immigrants' children should or should not be Americanized; that is, made more in the likeness of Cleveland's WASPs. Schoolrooms were the trenches. The Great Depression was about liquidity, the capricious lifeblood of capitalism. One day, before anyone knew he was there, a liquidity bandit was sucking up and hiding cash. The Standard Bank collapsed first. It had invested heavily in "the Florida Land Boom that wasn't" in the late twenties, leaving its depositors with worthless account books. Then, for similar reasons, cash disappeared from other banks. Cleveland's financial, labor and goods' markets ceased to function. Commercial activity was frozen. It's been said, "the Great Depression had to be endured to be believed." A 1931 survey revealed that of the 200 families in an average Cleveland neighborhood 66 had no visible means of support and 24 literally lived on garbage. By 1933 over half of Cleveland's work force was laid off and those still employed suffered pay cuts up to 50%. Philip Porter, a Cleveland Plain Dealer editor at the time, wrote: No one escaped the depression's deflation of earnings. Babe Ruth, the 1930 American League leader in home runs and a national idol, took a 25% pay cut in 1931.

5 Salary cuts and loss of jobs both helped and hurt Cleveland's labor movement. Unions promised job protection, so workers listened; but hunger gave employers an advantage in getting people to work for pittances. One of the most significant advances ever made by American labor, if not the most significant, was a victory at the Cleveland General Motors plant in 1937. A sit-down strike led to recognition by GM of workers' rights to join a union and negotiate working conditions with the company. GM, the icon of American capitalism, did not go easily into this revolutionary truce. It fought the workers in courts, used company goons and police to try and force workers out of plants, and had goons, maybe the police, too, threaten family members of the strikers. American business executives and some powerful U.S. Senators regarded unionization as a communist movement to seize the country. This rendering justified violently brutal treatment of unionized activities and glorified the violence as "patriotic" and "nation-saving." A catchy sound-bite rode the radio waves, "What's good for General Motors is good for America." There was some basis for linking unions to communism. Union ideology was at least as socialist as it was capitalist. One union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was dedicated to abolishing capitalism. The outstanding spokesman for IWW in Depression-era Cleveland was Frank Cedervall, chief organizer for IWW's Metal & Machinery Workers Industrial Union. Cedervall jolted businessmen with declarations on the essential incompatibility of workers' and employers' interests. "Eventually," he said flatly, "workers will take over and there will be no employing class." The Cleveland GM plant was the most strategic piece in this country-wide strike. It made bodies for all of Chevrolet's popular two-door models. Only when GM was sinking desperately in red ink with no end in sight did the company agree to work on a contract with the United Auto Workers union.

At the time I was not yet seven so the strike didn't capture my attention; in later years I was fascinated by the stories of what happened during the strike's forty-four days. First, all women were told to leave the plant. Then the men organized themselves into committees. It was important to their cause to appear orderly and civilized, to keep the plant clean and the machinery operational. No alcohol was allowed and each man showered daily. All of

these activities, along with entertainment, were managed by committees. There was a democracy of sorts in a kind of town meeting atmosphere. Looking at America from a working man's view, the 1930s were years of enormous progress. In 1930 a few laws existed to regulate the use of labor, such as the child labor laws, but the legal doctrine of "employment at will" dominated throughout the country, enabling employers to terminate any employee any time without incurring legal liability. Today virtually all states continue to provide some employment-at-will protection to employers, some more than others, but employers are constrained by public policy laws covering such topics as disabilities, age and race discrimination, and sexual harassment. My parents were not at all political or ideological. The only discussion of unions in our house was about my father's need to avoid union "checkers." Now and then he would work as a carpenter for a few days on a union-labor-only project. If the project was large enough, carpenters' union representatives might drop by to check on union cards. My father was never able to get one because the carpenters' union accepted very few new members from 1930 to 1939 and he didn't have the connections needed to be one of those few. PREVIOUS CHAPTER | TABLE OF CONTENTS | NEXT CHAPTER |