|

Ethnic Groups: Upstairs, Downstairs Cleveland was originally settled by white, English-speaking, Protestant Anglo-Americans from England, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Wales, with stopovers in New England and New York for some. They prospered off the land and gradually established the city as a significant industrial and banking center. During the second half of the 19th century they came to dominate Cleveland's social, economic, political, and cultural life.

The industrial revolution compelled them to import immigrants unlike themselves to provide cheap labor for the burgeoning plants and factories. They did so with mixed emotions because they feared the substandard norms of these new groups would erode their own. None were more feared than the Irish Catholics, the first large group of immigrants who were not Wasps. In 1845 a savagely cold, wet winter and spring in Ireland left a potato blight. Since the Irish diet consisted mainly of fish and potatoes, famine spread across the island, leading to mass emigrations, especially to America. Most of those who found work in Cleveland were from the poorest areas in Ireland. They were, as one historical account puts it, "remarkably unruly." The Cleveland Leader, an obdurately anti-Irish newspaper, reported that "between 1850 and 1870, 90% of the violent crimes in Cleveland were done by the Irish." Another account offers a mitigating explanation without denying the Irish were not an attractive group. My paternal grandparents, Michael, called "Paw" by all of us, and Theresa (Fogerty) Heaphey left Ireland for Canada when the harvest failures of the 1870s brought fears of another famine like the one in the 1840s. Paw said they went to Canada because "America waz too dollary fer us." The shock of all those Irishmen flooding into Boston and New York during the first famine scared the U.S. Congress into passing two Passenger Acts affecting all ships intending to dock in America. The first one limited the number of passengers a vessel was permitted to carry. The second increased the price of the cheapest passage to

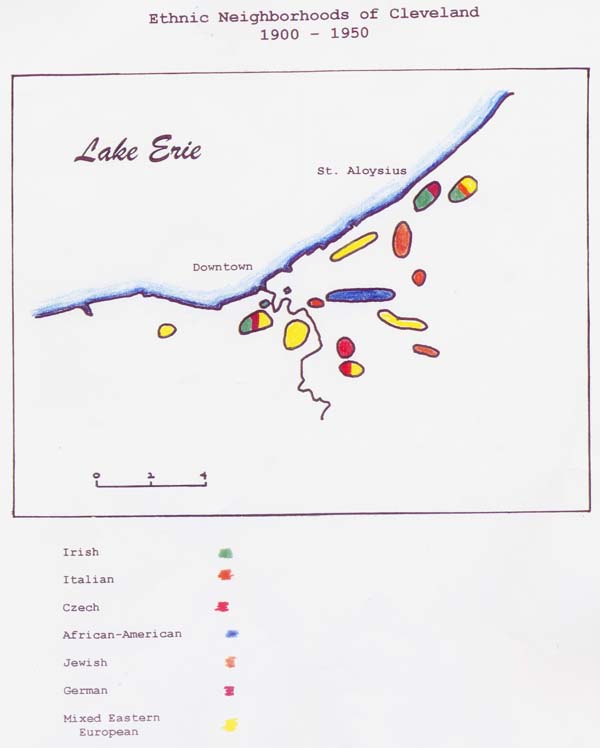

seven pounds, which was indeed "too dollary" for my grandparents. Though my grandparents could afford the price of admission to Canada they were nonetheless unwelcome. As an example, at that time the Common Council of St. John, one of the two Canadian ports where the Irish landed, unsuccessfully petitioned the British Government to take the Irish Catholics back to Ireland. The captain of my grandparents' ship bypassed St. John in favor of Grosse Isle to join a queue of 40 ships, carrying 15,000 Irish, many seriously ill, some already dead. As they waited English newspapers in Ontario and French newspapers in Quebec printed a leading statesman's warning, "These Irish are the most diseased, destitute and shiftless that Canada has ever received." My dad was born in Canada during the last decade of the nineteenth century, close to both Toronto and Montreal, where Irish-Catholics were shunned by English-speakers because they were Catholic and by French-speaking Catholics because they could not speak French. Church services were conducted in Latin and French. Schoolwork and church social activities were carried out in French. No one in my father's family spoke more than a dozen or so words in French. When dad was around nine years old, Abel Funeral Company, located in the neighborhood where I was to grow up, offered Paw work as a harness maker. "I tol' em" said Paw, "I'm already lookin' fer a horse knows the way cross the border." The family - there were five children -- settled in a Catholic mission manned by St. Thomas Aquinas Parish. Missions were defined by the Church as "outposts in wildernesses of need." About twenty years later a permanent parish campus was built and called St. Aloysius. I believe no member of the family other than my father bothered with citizenship rigmarole. My father had "papers," as he called them. St. Thomas mission was the next best thing to heaven for them. They were surrounded by Irish Catholics with a significant number of Catholic Germans thrown in. Catholic Germans were scorned by German Protestants but were admired by the Irish for their superb craftsmanship. No sense of "us and them" between Irish and Germans existed in my neighborhood. Two of my fathers' sisters married Germans. German and Irish kids played together in the streets. It

was a holy alliance untouched by intense vilification of Nazis during World War II. My father had three sisters and a brother still alive when I was a child. Only one had children then, Aunt Mae. She married Al Then, a German, and had three children, John, Dorothy, and "Junior," whose ages approximated those of Tom, Lois and myself. The two families lived within short walking distance and were always friends, especially the boys. As adults, John, "Junior," and Tom were fast friends. They bowled competitively as a team, played golf together, and, with their wives, partied at one another's homes in basements-turned-into dens by my father. Paw and my father seldom spoke of their past. They would make jokes - or what at the time we thought were jokes as in the case of "not being able to afford America" - but kept their personal histories to themselves. I think it was because of the suffering. Why resurrect memories of misery? Why relive humiliation? They secreted their past in self-deprecating jokes about being Irish, like, "the Irish are fair, they never speak well of one another." My grandfather also drowned his in buckets of beer. A poignant example of what for me is cheerless Irish humor was a story Aunt Mae would tell about my grandfather, always followed by laughter, hers and other members of the family. "One day, I was roun twelve, I was out with Paw. I get behin him cuz I stop to look at a pair a shoes in a store window. He come back to me, look'd at the shoes an kick'd me." My family didn't participate in Irish celebrations such as St. Patrick's Day. Like many other Irish we sublimated our background. Some years ago I read a doctoral thesis on American literature in which the author argued that F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mary McCarthy, and John O'Hara hid their Irish background and disdained the Irish in their works. Their heroes are thoroughly non-Irish, even when they are among the nouveaux riches; their Irish characters, ignorant and corrupt. What the Irish had run from in Ireland did not prepare them for the laissez-faire, democratic American scene. The English laws of 19th-century Ireland were designed to suppress Catholics, so Irish Catholic immigrants had little or no experience with property ownership. When they first arrived they saw no purpose in buying property, and they avoided farming because the famine had soured their trust

in the land. Their jobs were at the lowest rungs of organizational hierarchies. And the men had a problem with alcohol, which in those days was as cheap as water. For Wasp Clevelanders, ownership and frugal management of land, and sobriety, were fundamental values and virtues. Although they were given the right to vote, these Irish had no previous experience with representative government, orderly town meetings or consensus decision-making. As in other large cities, the Irish vote was courted both because of the numbers and Irish ignorance. The courtiers were not the established elite but upstarts who saw in the uneducated immigrants a quick road to socio-economic power. Unlike Boston and New York, Cleveland Irish didn't become functionaries in political machines until the following generation. By my time the father of a good friend, Tom Corbett, was a deputy county sheriff, a job reserved for members of a political machine. My friend and I hooked "Vote For" tags on doorknobs and passed out political party leaflets on street corners during election campaigns. Mr. Corbett told us that such activity would be rewarded with jobs when we were older, and possibly even with an appointment to West Point. Eastern Europeans, like my mother, came to St. Aloysius because of marriage or convenience of location to where they worked. Being Czech was one of my mother's two badges of pride. The other was her certainty that although she did not go beyond sixth grade and rarely read anything she knew everything worth knowing. The latter was one of her conceits of little substance. My mother's parents, Mary and Frank Zbornivicka, came to America from Bohemia around 1880. She was born in 1890, the last of six children. Cleveland was an accidental home for some Czech immigrants. Most of them came to farm in Nebraska, Iowa and Wisconsin, stopping over in Cleveland because of its geographical location and because it had a permanently-residing Czech community. My grandfather intended to buy and run a saloon with billiards tables in a Midwest farming town. When he saw the opportunities Cleveland offered he bought his business and settled there in St. John Nepomocene parish. The family name was used on parish rolls and for parish activities, but was changed legally to Zbornik. Eastern Europeans often changed their tongue-twisting names to simpler ones; sometimes for convenience, sometimes for affect. One of my mother's brothers went all the way to Born when he aspired to climb the hierarchy at General Motors.

Grandfather Zbornik was a well-educated tradesman in Bohemia when it was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, where education of tradesmen included learning German in addition to one's native language. Once in America he learned English quickly. Unfortunately he drank a considerable share of the saloon/pool hall profits, which dwindled daily because he belittled customers he considered inferior to himself, of which there were many. Though soon separated from his business assets he clung tenaciously to his vanity. After a few years of surviving financially by providing legal-document translation services to other Czechs he took a job as a floorwalker at The May Company, a major department store in downtown Cleveland. My mother described him as perfectly fitted to that kind of work, where a dignified appearance was more important than anything else. In those days floorwalkers dressed like Fred Astaire dancing at a formal affair, complete with a fresh flower in the left coat lapel. He made two trips back to "the old country." My mother said he would just announce when he was going and provide an estimated time of return. My grandmother was not invited. Rumor had it he was disgusted with her for not learning so much as a word in English. Her resolve to speak no English remains a family mystery. My mother and her family considered themselves a cut above other Eastern European groups, particularly Slovaks; who, in turn, spoke of themselves as better than Czechs. The Czech-Slovak feud was typical of Eastern European groups. They brought their old-world disputes with them. The Czechs and Slovaks were non-violent, but groups like Serbs and Croats brawled in the streets. Cleveland's elite held all eastern Europeans in contempt, bunching them together with the derisive name of "Bohunk," a combination of Bohemian and Hungarian. In this they were encouraged by "Social Darwinism," a theory of human evolution that infiltrated American thought and public policy in the early 20th century. According to one variant of Social Darwinism, human evolution had culminated in the Anglo-Saxon race. Anyone who did not come from northwestern Europe was genetically inferior. As I've already suggested, Irish Catholics were not included in the winning category. In 1907, the U.S. Senate formed The Dillingham Commission to study consequences of immigration. The Commission's 42-volume report pointed out that prior to 1840 the vast

majority of immigrants were Anglo-Saxons, whereas after 1875 the vast majority were not. The alarming rise in crime and social unrest in turn-of-the-century America, concluded the Commission, was due to this difference. A few years later, after World War I and the Communist revolution in Russia, the "Red Menace" increased Wasp anxiety about eastern European immigrants, who, in addition to their genetic shortcomings, were now portrayed as "communism spreaders". An event on May 1, 1919, fueled Clevelanders' anxiety about working-class immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. Socialists and trade-union members paraded, carrying red flags and wearing red clothing, to celebrate the anniversary of the revolution in Russia, to promote the mayoral candidacy of Charles Ruthenberg, leader of Cleveland's Communist party, and to protest the recent jailing of Eugene Debs, a Socialist Party leader. Debs had been charged and convicted under the wartime Espionage Act in Cleveland for an antiwar speech given in Canton, Ohio. Staunch American nationalists physically challenged the marchers to lower the red flags "or else." Fists led to more lethal weapons, eventually involving mounted police, army troops and tanks. Similar disruptions happened nationwide that day but nowhere was there as much violence as in Cleveland. Newspapers reported that of the 116 demonstrators who were arrested only eight were native-born Americans, arousing the city's civic organizations, Protestant clergymen and other members of the elite to call for restricting immigration, limiting parades and more rapid Americanization of immigrant labor families. In what was presented as an urgent matter of national security, the U.S. Congress, in 1924, passed a quota law, drastically reducing the numbers of immigrants from eastern Europe to three per cent of the prewar level. Despite her unfavorable comparisons of Irish to Czechs, my mother enjoyed socializing with my father's family more than with her own. The Heaphey clan gathered at "the house", an Irish expression for wherever one's grandparents lived, for holidays, birthdays, and other special occasions. It was always a crowded affair and followed traditions such as a generous meal with even more generous desserts. After dinner the men played poker, the women played canasta, and the children played outside or went to a movie if it was raining.

My mother's cooking and pastry-baking were admired by the Heaphey women, most of whom were inept in a kitchen except when chatting over coffee. My father's mother and sisters had extraordinary talents as conversationalists. My mother said, "they know how to make you feel happy." It never occurred to her, I'm sure, that they did not give advice, they listened and consoled or applauded, whichever was appropriate, whereas she was nothing if not an advice-giver. She spoke often in adages. Some of her favorites were "time is money," "you are who you think you are," "watch your pennies and your dollars will take care of themselves." She delivered them in crisp, emphatic tones while wagging her right index finger as though it were proving her point. While most of her maxims were, and remain, sound advice, she seemed to think she was speaking famously. So her pronouncements took on a comical quality. Sometimes I saw in them thinly, if at all, camouflaged criticisms of my father. As is the case generally with people who think they sell their point with an adage, my mother was indifferent to consistency. When it suited her purpose her wagging finger would chide, "Don't hide your achievements under a bushel basket. No one can see them there." But when the "A"s appeared repeatedly on my report card, she allied herself with a contradictory bromide, "After you've climbed to the top of the ladder, the only place to go is down." When we did visit my mother's family members she was usually tense throughout the visit, feverishly and unsuccessfully policing my behavior, and often, back home, she would sit and weep because their houses were grander than ours. She was downright jittery when we visited Aunt Mary, her older sister, who was so prune-faced I would stare at her as she sat in her rocker, wringing her hands in despair with my rudeness. My mother would say, "Jimmy, why don't you go outside and play." I'd reply, "Don't want to," and intensify my stare. Then came, "Jimmy. Go outside!" One time when we left her house, and my mother was building up to a teary remembrance of the furniture, my father said to me, "Ya know, Jimmy, ya gotta learn to stop upsettin people so much. I thought if Aunt Mary wringed her hands one more time they'd a fell off." Tom, Lois and I laughed and laughed. Then he added, enjoying the moment, "well, at least ya didin tell her, like ya said ta mizzus Madigan,

people with faces like hers don go ta heaven. Jeez ya set her hair on fire." I don't know how my father was able to pull humor out of those situations. He had to have been feeling lousy because Aunt Mary thought he was quite inferior to her family and never withheld those feelings from him. When we would arrive at her house she would say curtly, "I didn't see your car," knowing we came by streetcar. One of her favorite comments on my behavior was, "You're so Irish, like your father." She was quite unfair. My father was always well behaved. What I never found out was how my father felt in his private thoughts about class, race and color distinctions. On the outside he appeared tolerant of all others to a fault. Even his devout Catholicism was not used by him to compare himself favorably to another. His favorite joke was: This guy goes to heaven and is taken on a bus tour of the place by St. Peter hisself. As they go through the clouds Peter he tells 'em what they're looking at. "Over there," he says, "there are the Presbyterians. Over there, there are the Episcopalians. Here be Methodists." It goes like that until they come to a cloud set off a bit from the rest. Peter says "shhhhhh. Be quiet, now. Over there, there's the Catholics. They think they're up here all by thimselves." My mother admired Jews because "they have self-confidence and know how to make money." The man who owned the company where my father worked was Jewish, as was our landlord, our doctor and our pharmacist. Our neighborhood bordered on a large Jewish one. Most of the Jews who were prosperous were second or third generation Germans, originally from the small town of Unsleben, Bavaria. They were accepted more or less as economic and even social peers by Cleveland's leaders because they had money and professional status, and, as followers of Reformed Judaism, wanted to blend in. The Jews who came to Cleveland in the 20th century were running from persecution and economic deprivation in Russia and Poland. The ones I knew were paper-rag men or door-to-door salesmen of odds and ends from pushcarts. The former were a bit anachronistic, even on our street. They came slowly down the street in horse-drawn carts yelling "Payyyy-paaaa-rex, payyyy-paaa-rex." They had long scraggly beards and dressed austerely in dark colors. If you called

one he came to your back door with a tattered burlap bag and hand-held scale, the exchange being pennies for pounds. They were suspect to Cleveland's leaders because they followed Orthodox Judaism and spoke Yiddish. Like Catholics, they presented an ill-omened cultural threat. PREVIOUS CHAPTER | TABLE OF CONTENTS | NEXT CHAPTER |