Cleveland's First Infrastructure:

The Ohio & Erie Canal

Section 1: Discussing a Passage

During the 17th and first half of the 18th centuries, European knowledge of the river ways of Ohio spread through a web of contact between such diverse groups as indigenous inhabitants, French explorers, Moravian missionaries, unlicensed English Indian traders, and Pennsylvania explorers.

From front piece of Washington Irving's Life of Washington, Volume V, 1859

While in his teens, George Washington trained and worked as a surveyor in Virginia. In 1753, at the age of 21, he volunteered to travel as emissary on behalf of Virginia Governor Dinwiddie to ask the French to leave the Ohio River Valley. Returning to Virginia to convey a message of the French refusal to the Governor, Washington took with him first-hand knowledge of the Ohio River region.

Writing in the 1780s about the potential of a passage between the Ohio River and Lake Erie, Washington drew on the accumulated knowledge of previous generations, and on experience he had acquired before the French and Indian War and American Revolutionary War.

In several letters, Washington expressed a keen interest in determining a passage which would connect the Ohio with Lake Erie.

To THOMAS JEFFERSON

Mount Vernon, January 1, 1788

Dear Sir: I have received your favor of the 15th.of August, and am sorry that it is not in my power to give any further information relative to the practicability of opening a communication between Lake Erie and the Ohio, than you are already possessed of. I have made frequent enquiries since the time of your writing to me on that subject while Congress were sitting at Annapolis, but could never collect anything that was decided or satisfactory. I have again renewed them, and flatter myself with better prospects of success.

The accts. generally agree as to its being flat country between the waters of Lake Erie and Big-Beaver; but differ very much with respect to the distance between their sources, their navigation, and the inconveniences which would attend the cutting a canal between them. From the best information I have been able to obtain of that Country, the sources of the Muskingham and Cayohoga approach nearer to each other than any water of Lake Erie does to Big-Beaver. But a communication through this River would be more circuitous and difficult; having the Ohio in a greater extent, to ascend; unless the latter could be avoided by opening a communication between James River and the Great Kanhawa, or between the little Kanhawa and the West branch of Monongahela, which is said to be very practicable by a short portage. As testimony thereof, the States of Virginia and Maryland have opened (for I believe it is compleated) a road from the No. branch of Potomack, commencing at, or near, the mouth of Savage River, to the Cheat River, from whence the former are continuing it to the Navigable Water of the little Kanhawa.

The distance between Lake Erie and the Ohio, through the Big-Beaver, is, however, so much less than the rout through the Muskingham, that it would, in my opinion, operate very strongly in favor of opening a canal between the sources of the nearest water of the Lake and Big-Beaver, altho the distance between them should be much greater and the operation more difficult than to the Muskingham. I shall omit no opportunity of gaining every information relative to this important subject; and will, with pleasure, communicate to you whatever may be worthy of your attention.

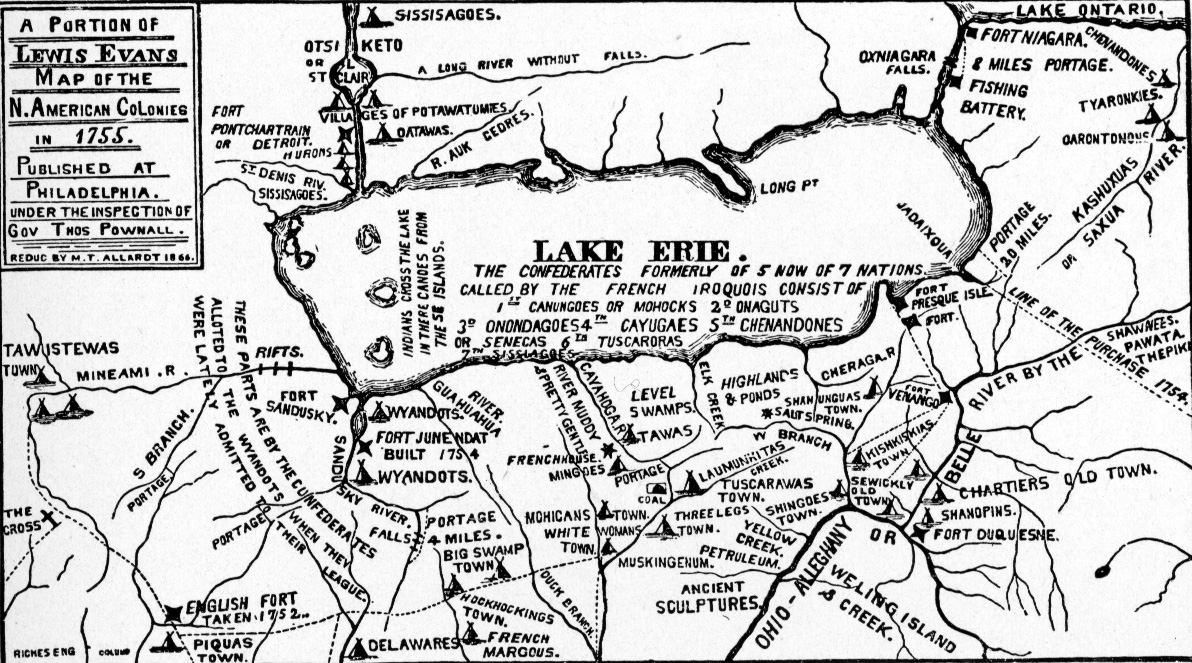

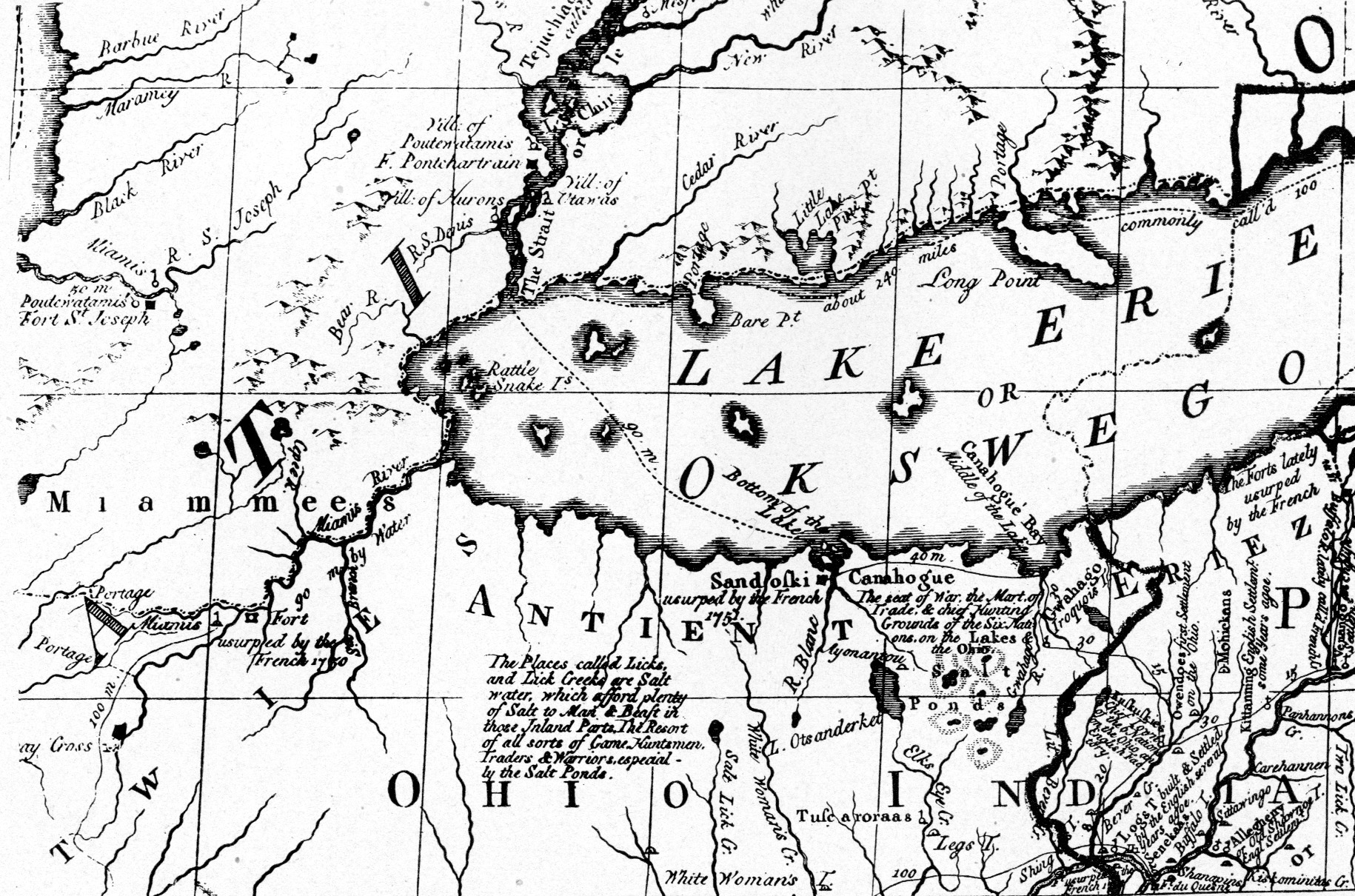

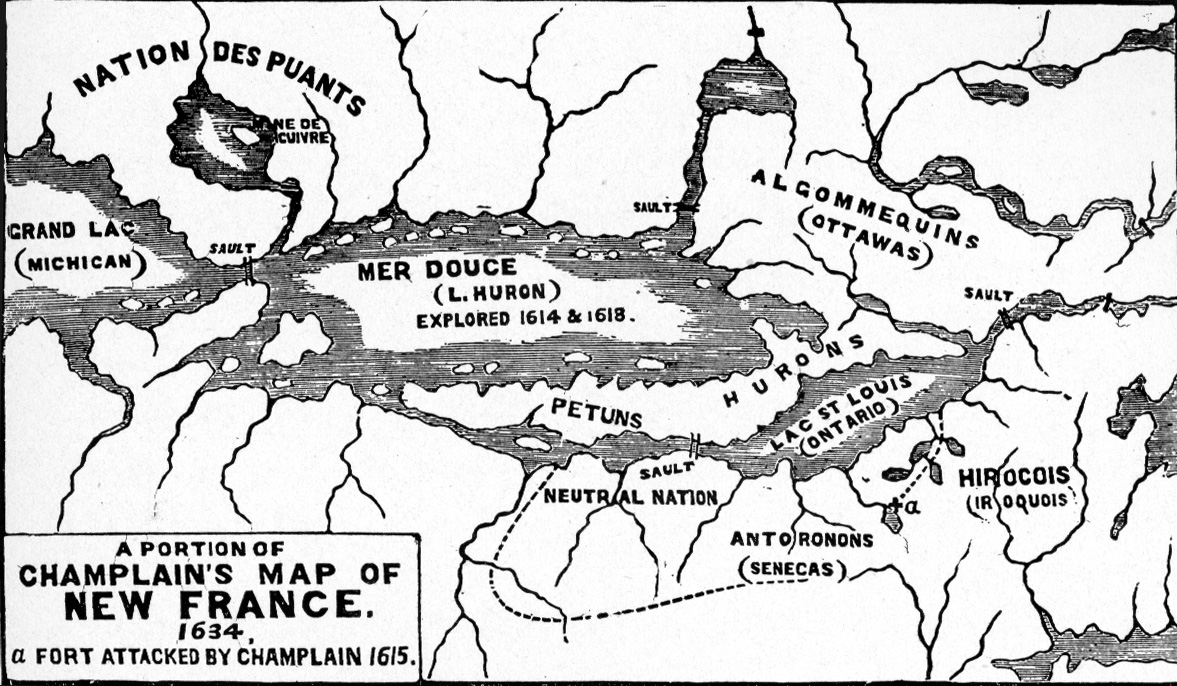

Early maps demonstrate European attention to the area which would become Ohio.

Champlain's Map, 1634, "the first made of the

Lake Regions" (from A History of Cleveland Ohio,

Vol. I, by Samuel P. Orth, facing page 82)

Indigenous Peoples, The Western Reserve, and Moses Cleaveland

In 1786, Washington wrote to Richard Butler inquiring about the disposition of Western Indians, the politics of the people along the Ohio, and comparative distances of routes "from the River Ohio to the Lake itself" (letter dated November 27, 1786). That same year, the state of Connecticut ceded to the United States most of its western lands, which by charter stretched as to the western shore, keeping a Reserve in what is now northeastern Ohio.

In 1795, the U.S. Army defeated the intertribal Indian resistance at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on the Miami River in northwestern Ohio. As a result, intertribal leaders signed the Treaty of Greenville, surrendering their claim to the lands east of the Cuyahoga River. Also in that year, Connecticut sold most of the reserved lands to the Connecticut Land Company for resale. In 1796, Moses Cleaveland, one of the company's first directors, led a survey party to the Western Reserve, negotiated with the Iroquois for control of lands east of the Cuyahoga river, and founded the settlement of Cleveland.

Cleveland's First Infrastructure is a project of Cleveland State University Library Special Collections, and was made possible by a grant from the Cleveland Section of the American Society of Civil Engineers. It seems appropriate that this exhibit, which highlights the achievement of civil engineers of the early 19th century, premiered during National Engineers Week and on the eve of the birthday of military engineer and land surveyor George Washington. We hope that this site will serve as a gateway through which people can learn about the canal, identify resources for further investigation of canal engineering and history, and find opportunities to visit preserved areas of the Ohio & Erie Canal in Ohio.